My coauthor Ken Bloom and I will be presenting on our book EUBIE BLAKE: RAGS, RHYTHM, AND RACE at the Maryland Historical Society, whose archives hold Eubie’s papers, in a virtual online discussion that is open to all. The presentation will be on Thursday, May 6th, at noon. Here’s a link with info about it:http://MCHC Registration Page Link: https://www.mdhistory.org/calendar/eubie-blake-a-conversation-about-rags-rhythm-and-race/

Listen to Our Podcast!

Here’s the inaugural of our projected podcast series, EubieCast. In this episode, we discuss the life and career of Lottie Gee, the now-forgotten star of Shuffle Along.

A New Virtual Presentation Coming Soon!

Lottie Gee, Part 2

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!

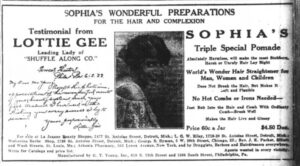

Gee was an ideal performer to play the controversial role of a romantic lead in Shuffle Along. Besides her great talents as an actress and singer, she was fair-skinned with straight hair, which she wore in the popular style of the day. She could easily have passed for white. In this way, she fit into the standard for black chorines in general who were expected to be light skinned and conventionally attractive. Drawing on her conventional good lucks, Gee landed an endorsement deal with “Sophia’s Triple Pomade,” a hair-straightening treatment that promised to “make the most Stubborn, Harsh, or Unruly Hair Lay Right.” Gee’s photo appeared in advertisements that ran in the African-American press, along with a testimonial letter praising “the wonderful merit of [this] beauty system.”

Once the show hit Broadway, Blake set Lottie up in her own apartment, while continuing to live with his wife. Eubie was impressed with her talent and theatrical experience, as well as her good looks:

I guess I have to say I was smitten. When I was at a party and she was there, she acted like she barely knew me. Called me “Mr. Blake” because, of course, nobody is supposed to know I’m livin’ with her, see. But she never came near me in public. Alone though, she called me “Daddy.” Poor Lottie! I never bought her a thing! I put a piano in her house, but just so I could teach her the new songs. Ten years I spent with that girl…

Eubie’s wife Avis was, in his words, “no dummy,” and soon realized that the pianist was maintaining a separate household with the young starlet. According to Eubie, when a friend asked Avis how she could put up with Eubie’s philandering, his wife was more than able to stand up for herself:

“Honey, you see that l’il ol’ box on the vanity? Just go over there and open it.”

Filled with diamonds and emeralds, the visitor found.

“My husband, that no-good nigger gave me those. Now, baby will you just slide open that closet door and count the fur coats?”

Five.

“Kitten,” Avis pursued, “What are you going to do in the morning?

Well, since it was a week-day, she’d go to work.

“Not me, kiddo!” Avis assured her guest smugly. “I’m stayin’ right here in bed until I feel like gettin’ up. That no-good nigger husband of mine bought me those jewels and those furs. He takes care of me so I don’t have to lift a finger . I don’t have a maid, because I don’t want on around the place, but I’ve got a car and a chauffeur. I can’t drive, you know. And I’m gonna worry what the no-good nigger might be doin’ behind my back? No, Gal, you need to get you a low-down cheater like my Eubie.”

According to Blake’s biographer Al Rose, the two jealous women tried to control Blake’s sex drive in an unusual manner; before he left home, Avis would force him to have sex with her until he ejaculated, and then Lottie would do the same every time Blake was about to leave her apartment.

The relationship of Gee and Blake created friction not only in his marriage but with his partner Noble Sissle, who took a much more traditional view of the sanctity of marriage—this despite his own affairs with chorus girls. In an undated letter, Sissle scolds Blake for his extramarital flings, advising him that he’s risking the future of their partnership:

Eubie I hope you have your family troubles straightened out. Don’t let no other woman break up your home. The woman you took before Gods sacred shrine as your wife is the only woman in the sight of God and man beside your relatives you have any right to take care of. Now I have made for myself a name among the best of New York City and I don’t intend to be disgraced by any of your affairs so I give you warning. Unless you are straight with your wife and decided to let that other woman alone for life as far as living with her is concern than its all off.

Of course, Blake wouldn’t—or perhaps couldn’t—change his behavior to please his persnickety partner. Sissle’s upbringing as the son of a minister made him appear to Blake to be a humorless scold. The successful partnership was starting to show the first signs of friction, which would eventually lead to the duo splitting up.

What Happened to Lottie Gee? Part 1

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!!

When Shuffle Along opened in May 1921, it was a surprise commercial and artistic success. The first musical comedy with a script, songs, and dance numbers written by African-Americans—and an all-black cast—Shuffle Along revolutionized the Broadway musical. It was the first musical to present Blacks as “real people”—going far beyond the popular minstrel stereotypes. And the star of the show was actress Lottie Gee—one of the most successful black singers and dancers of the era, having established herself both on the New York stage and abroad. Gee’s performance lit up the stage and her picture was splashed across newspapers around the country—both in the black and white press. But strangely after her immense success in Shuffle Along—which ran for over 500 performances in New York alone—Gee disappeared from theatrical history. Unlike other female stars who made their Broadway debuts in the show—including Gertrude Saunders, Florence Mills, and Josephine Baker–she never made a record, never appeared in a short film, and by the late ‘20s was virtually forgotten.

Born Charlotte M. Gee in Millboro, Virginia, on August 17, 1886, Gee worked her way up from chorus girl to leading lady. Gee made one of her first appearances as a chorine in the 1909 touring cast of Cole and Johnson’s The Red Moon. Her light complexion allowed her to appear as a “Gibson girl” in the show’s chorus, a role not usually associated with black actresses. In 1911, she partnered with singer/dancer Effie King, touring as a vaudeville duo. A reviewer writing in the African American press praised them for weathering the difficult conditions faced by black performers and succeeding on the stage:

In no other field have colored Americans with artistic aspirations found the road to success so hard as that leading to prominence upon the stage. As a rule, those who have selected the stage for their professional career have been given very little consideration by our writers and critics. . . . [While] the profession has in the past merited severe criticism… it has improved with time . . . Conspicuous on the rol[e] of those who are endeavoring daily to raise the standard . . . [are] Misses Effie King and Lottie Gee . . . as a refined singing and dancing act. . . . These talented young women . . . have excellent voices and know how to use them. The act is beautifully costumed and staged with artistic taste.

The reviewer used code words like “refined” and “artistic taste” to indicate that the performers were a notch above black-faced minstrels, representing an advance beyond earlier stereotypes. The reviewer also proudly noted that both women came from educated families and had sung in their church choirs in their younger years, subtly countering the stereotypes that female performers were low-class. The review concludes with the solidly middle class endorsement that “both [performers] own property, thus showing that their efforts have not been in vain.”

In 1913, Gee married pianist Wilson Harrison Kyer, known by the stage name of “Peaches.” Originally from Charleston, South Carolina, Kyer was musical director for the well-known black touring company The Smart Set for their 1911-1912 season. In 1914, Kyer and Gee entertained for a period at Hayne’s restaurant in New York City, but after that notices of Gee appearing on stage ended; perhaps she retired while Kyer supported the family. Whatever happened, the marriage didn’t last; Kyer apparently left her in 1919, but the couple were not formally divorced until 1924.

Gee returned to performing by the late teens, and appeared at least occasionally as a vocalist with Will Marion Cook’s Syncopated Orchestra. In late 1919, she travelled with that group to England, where she performed for much of the next year. She then toured France, Italy, and Asia. Gee reported to Josephine Baker that playing in Europe was a joy and that she encountered very little racial prejudice. In fact, newspapers in France reported that the government would deport any Americans who made a scene in French nightclubs where “management permits Negroes to dance with white girls.” Her popularity was so great that she returned briefly to New York for an appearance at the Lafayette Theater that August, winning rave reviews in the African-American press:

Miss Gee has an act that can bear rigid inspection and severe criticism from every angle. This young lady is attractive in appearance and her costumes, particularly that creation of black which she dons toward the close of her skit, make her doubly pleasing to gaze upon. She sings and dances well, showing ability to render both ragtime songs and high class ballads….Anyone who can do as strong a single as Miss Gee can hold their own in fast company—musical comedy especially.

The reviewer compared Gee’s performance to Abbie Mitchell, one of the great stars of the turn-of-the-century black theater (and Will Marion Cook’s wife). She returned permanently to the states that December, resuming work on vaudeville.

In 1921, Gee was hired to play the love interest in Shuffle Along. Eubie told his biographer Al Rose that Sissle and he were so anxious to have Gee in the title role that they paid her expenses and provided lodging for her throughout the rehearsal and try out period for the show. It’s likely that her recent successes in London and New York added to her marquee value. Blake was immediately smitten with the young singer/actress, and she would spend the next decade living as his mistress. Her involvement with Blake would have repercussions on the development of her career—as we shall see.

Recording for Pathé

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!

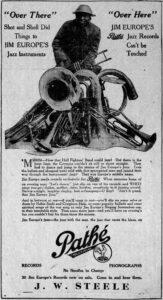

Before leaving to serve in World War I, James Reese Europe’s band was signed to Pathé Records to make a series of recordings. Sissle joined the group as its vocalist for the group’s recordings in spring 1917 in between attending training camp with Europe’s regiment. Among the numbers he recorded was the song “Good-night Angeline,” written with Blake and Europe; a sentimental ballad, the song remained in the Sissle and Blake repertoire for decades. On the 22nd of June 1917, Sissle and Blake signed a separate deal with Pathé. Royalty statements for the duo were issued for three numbers—“Good Night, Angeline,” “He’s Always Hanging Around,” and “Mammy’s Little Cho’late Cullud Chile”–for sales from October 1917 to July 1919. The recordings sold well on their initial release, with each of the first two titles selling about 2400 copies and the third doing nearly 1000, but then the numbers dropped to the low 100s for the remainder of the reported periods.

In addition to recording with Sissle, Eubie recorded on his own in fall 1917 with three 78s issued in 1918 under the name of The Eubie Blake Trio. The group featured Blake and an unknown second pianist (possibly pianist Elliott Carpenter who had also worked with Jim Europe’s band and would remain a lifelong friend of Eubie’s) as well as a barely heard percussionist (perhaps Buddy Gilmore, the percussionist from Europe’s band). Another possibility is that the drummer was the comedian/vocalist Broadway Jones, with whom Blake said he was performing in New York during the war years. (Jones became Blake’s performing partner in the later ‘20s and early ‘30s.) The description in Pathé’s catalog makes it sound like they were a regular performing unit:

The Eubie Blake Trio comprises an organization of three extremely clever colored musicians whose talents in entertaining the “400” and ultra-fashionables of N.Y.C,. are extremely in favor and much sought after. As exponents of “jazz” and “ragtime” piano, two of its members are “King Pins.”….The two selections …afford fine opportunity for display of real “down south” ragging both on the piano and in the drummer.

In all, three selections made that day can be definitively attributed to Blake and his trio, the novelty song “Sarah from Sahara” (composed by Hugo Frey and published in 1918) and two novelty rags, “American Jubilee” (written by Tin Pan Alley composer Edward B. Claypoole in 1916, with snippets of bugle calls and patriotic melodies like “Yankee Doodle” thrown in for good measure) and “Hungarian Rag.” All were marketed by Pathé as fox trots for dancing.

On “Hungarian Rag,” a novelty written by Julius Lenzberg in 1913, one pianist plays the steady bass part while the second pianist handles a highly ornamented part in the upper keyboard, including many fast scale flourishes. Judging from Blake’s recordings made a few years later, it is likely that Eubie was playing the upper part that is more prominent than the lower accompaniment. Just as when he cut piano rolls a few years later, Eubie may not have selected this piece to record, but rather was responding to the producer’s needs for a popular item. For this reason, there’s not much distinctive about the playing here beyond what would have been heard from other novelty pianists of the period, such as Zez Confrey. It is interesting to note, however, that the piece features a descending, harmonized progression in its first part; Blake used a similar figure in his own compositions of the period.

Brown Skin Models of 1955

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!

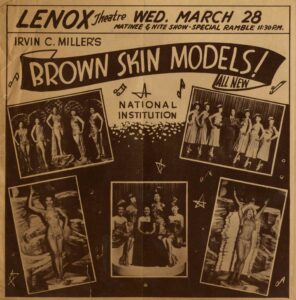

After the failure of the Broadway revival of Shuffle Along in 1952, Flournoy Miller and Eubie continued to collaborate together on new songs, hoping to launch another show. In 1955, Miller’s brother Irvin invited the duo to score the latest edition of his long-running Brown Skin Models revue. These revues combined comic sketches, song and dance, and parades of scantily-clad, light-skinned girls that Miller had produced since the 1930s as inexpensively as possible to tour the country. The plan for the new show was to have a slightly higher quality of staging and scenery, with the idea of perhaps being able to attract Broadway interest. The show was to star Miller and his regular sidekick Mantan Moreland, along with singer-dancers Mable Lee, Canadian-born Valerie Blake, and Lee Richardson, the singing Rhythmaires, and “fourteen beautiful chorus and show girls and Smalls Boykin and his dancing boys.” Blake was to lead a 12-piece orchestra for the show.

Miller and Blake wrote an entirely new score for this show. Their songs were inspired by well-known hits (“Old Man River Is Lonely Now”), as well as crafted to suit novelty numbers (“The Thrill I Felt in Sunny Spain,” designed to accompany a Spanish-styled dance number, and the minstrel-flavored “Mississippi Honey Moon”).

Irvin Miller’s plan was to prevue the show at Washington’s Howard Theatre, before taking it to New York’s Apollo and then on the road, hoping eventually to reach Las Vegas and the West. He pitched the show to the African-American press as a return to the glory days of high-class revues, like the Blackbirds series that were major hits on Broadway. As the critic in the Chicago Defender noted:

The attempt to revive the dying Sepia show circuit will rest on the beautiful shoulders of “Brown Skin Models”…On a toboggan since the closing of the Lafayette Theatre [in New York] many years ago, the vaudeville show circuit has dwindled from forty-two consecutive weeks of theater to an alarming one. Even that one, the Apollo theatre here, becomes none when summer rolls around. Unless something is done to check the decline the complete death of this once great entertainment and avenue for the development of Negro talent is but a few seasons away.

The Defender’s critic suggested that the reason for the decline of interest in African American revues was the lack of “the entertaining family type shows with original music, solid performers and pretty girls which inspired producers to take to Broadway in the past.” No mention was made of the fact that this style of entertainment—particularly in its broad, racial humor—was becoming increasingly outmoded by changes in society and the growing clamor for Civil Rights.

Despite Irvin Miller’s assertion that the new Brown Skin Models would be a true book production, the only really scripted scene was a sketch by Miller and Mantan titled “The Poker Game” that was probably reworked from earlier routines that Miller had written. The rest of the show consisted of solo songs and production numbers, a few dance routines, and the requisite leggy showgirls.

When the show had its first performances in Washington, DC, Sissle sent a thoughtful telegram to Blake, Miller, and the cast, congratulating them on their opening:

34 Years ago almost to the month right here in the Howard Theatre four guys with a dream and with no one to disturb them and surrounded by faithful talented cast who believed in them saw their dream become a reality and a gem of an artistic entertainment was born … well here[‘]s hoping that once again within these historic walls there will be a rebirth of that same spirited breathless dancing harmonious soulfull [sic] singing and uproariously clean comedy that will once again bring to the legitimate theater that wholesome original style of entertainment the world is yearning

However, other than the performances in Washington and Harlem, the show never hit the road and there was no interest expressed in bringing it to Broadway.

Blackbirds of 1930

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!!

In the annals of theater history, there are many colorful characters among the actors, agents, producers, and critics who populate the Broadway scene. Lew Leslie was undoubtedly one of the most eccentric, with a meteoritic rise and fall worthy itself of a Broadway show. Leslie began his career as a vaudevillian in partnership with Belle Baker, who would become his first wife, but quickly switched to being an agent/producer. His big break came when he was hired to produce a revue at Broadway’s Plantation Club in 1922, and was able to lure away Florence Mills from the cast of Shuffle Along to be his star. Suddenly finding a mission in life, Leslie became a champion of African American performers.

In 1926, Leslie took Mills to England, along with several other performers including comic-dancer Johnny Hudgens (late of the ill-fated Chocolate Dandies). Titled from Dover to Dixie, the show’s highlight was Mills’ performance of the song “I’m A Little Blackbird,” which she sang after emerging from a giant pie. Capitalizing on the song’s success, Leslie next placed Mills in a revue titled Blackbirds of 1926, which played in Harlem and then Paris. However, just as she was achieving great success, Mills tragically died in 1927, so Leslie had to find a new star for his next production, Blackbirds of 1928. He hired Adelaide Hall to fill the part, along with dancers Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and “Peg Leg” Bates. Leslie hired the white songwriting team of Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh to compose the songs, and several became major hits, including “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” The show broke records for an all-black revue on Broadway, with over 500 performances. However, Leslie worked his cast mercilessly, adding midnight shows to capitalize on the production’s success. He also paid poorly and irregularly—not unusual for the time—so that eventually Hall left the production in disgust after it went out on the road.

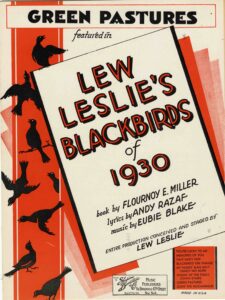

Perhaps under pressure to live up to his image as a champion of black artists, Leslie decided to produce Blackbirds of 1930 using all black-talent, even behind the scenes. He turned to Flournoy Miller, who had recently split with his stage partner Aubrey Lyles. Lyles had decided to move to Africa to escape American racism, leaving Miller high and dry. In Lyles’ place, Miller partnered with Mantan Moreland, who would remain his sidekick for several decades. Miller was hired to write the show’s book, which like most revues was fairly loosely constructed to accommodate the various acts. Ethel Waters—who had achieved great success in Harlem’s nightclubs—was to be the leading lady for the production. Also included were the vocalist Minto Cato, the dance duos the Berry Brothers and Buck and Bubbles, and Blakes’s partner Broadway Jones.

Leslie came to Eubie with a rich offer to compose the score: a $3000 advance (about $45,000 in today’s dollars) to write 28 songs from which several would be selected for the show. Blake was also hired to conduct the orchestra at a promised salary of $250 a week ($3750 in current dollars). This was very good money for the period, considering the Great Depression was just beginning.

For the lyricist, Leslie turned to Andy Razaf, who had scored several hits in partnership with the pianist/singer Fats Waller, among others. Razaf was among the most sophisticated lyricists of the period, bringing a unique combination of wit and a bit of a political edge to his work. When writing for Waller, Razaf said, “you can almost hear how he’s going to sing your words while you’re still writing them down on paper.” His job was to fashion lyrics that fit Waller’s larger-than-life stage personality. But writing with Eubie would prove to be different: “When you’re writing to his music, you never know who’s going to sing it…When I write for Eubie, I think of big sets, a chorus line, elaborate costumes. Of course, Eubie’s melodies lend themselves so perfectly to sophisticated lyrics, and they’re sort of a challenge, too, because musically he’s so far ahead of most contemporary popular composers.” Blake and Razaf hit it off immediately, with the lyricist’s sense of humor strongly appealing to Eubie. The two spent the winter working together, holing up at Andy’s mother’s house in Asbury Park, NJ.

Blackbirds of 1930 was a hugely ambitious production. Typical of Leslie, he couldn’t stop tinkering with its various components, adding new segments and dropping others, while also fussing over every detail—even leaping into the orchestra pit during rehearsals to show Eubie how to properly conduct. Eubie found Leslie difficult to work with throughout the rehearsal process and began to suspect that Leslie was slightly unbalanced. “Somethin’ went wrong with Leslie, somethin’ went wrong with his head,” Eubie told Razaf’s biographer Barry Singer. Dancer John Bubbles noted that throughout the production there was a lot of friction between Leslie and Blake: “Eubie wanted things to go the way he wanted to go, and Leslie wanted things the way he wanted to go.” Bubbles concluded however that ultimately it was Leslie’s show and he could make any changes that he wanted whenever he wanted to do so.

The show’s big hit was the song “Memories of You,” which was introduced in this opening scene by Minto Cato, who was known for her amazingly high vocal range. In the words of the Chicago Defender, for Cato a “high C is low,” and the song was custom tailored to show off her vocal chops. Oddly, Waters, not Cato, made the first recording of the song in August 1930. She says in her autobiography that she was imitating the popular warbling style of Rudy Vallee in her performance, and indeed her exaggerated enunciation and totally unsyncopated reading of the lyrics is much in the style of this popular crooner. Eubie would later regret crafting the song specifically for Cato, saying the song’s wide range limited it to a select group of performers. Nonetheless, it became a hit for Waters and Louis Armstrong, who covered it with his big band, and in the mid-‘50s, it was revived as an instrumental by Benny Goodman, hitting the charts again.

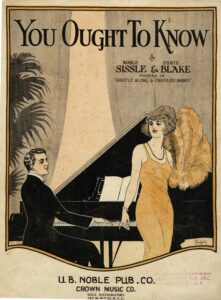

“You Ought to Know”

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!

Sissle and Blake created an new set of songs for Chocolate Dandies, and Eubie would remain adamant throughout the rest of his life that they far surpassed their original hits from Shuffle Along. However, most of the critics found the songs not to be as catchy as those in the duo’s first hit show. This may have been exacerbated by Sissle and Blake’s second act interlude—which on opening night came at 11 PM in the sweltering heat—during which they reprised the earlier show’s hits. The perhaps unintentional outcome was to unfairly place their new songs in competition with their best-known and successful ones. Some critics thought the new songs were “perhaps of a higher class” and “the harmony and the melody is at all times beautiful.” But this again was a backhanded way of indicating they missed the more “negro” flavor of the duo’s earlier songs, preferring them to write in the acceptable idioms of ragtime and jazz, rather than emulating “straight” Broadway composers. The reviewer in Variety bluntly summarized the general consensus of the white critics, saying that the show’s “pretensions toward white musical comedy [are] achieved at the expense of a genuine Negro spirit.” The critic noted “there is plenty” of “white folks entertainment,” but that “good darky entertainment” was rare—and this is what African-American entertainers should stick to doing. This would become a common theme in reviews of black musical productions going forward.

Eubie commented that when the show previewed in Boston, one of the new songs “Million Little Cupids in the Sky,” was removed from the production at the insistence of the local management who felt the song was “too high class” for a Negro show. In later life, Eubie singled out “Dixie Moon” from the show as one of his favorites of all of his songs; while Sissle’s lyrics flaunted all the typical imagery of minstrel-era songs, Blake’s music showed unusual sophistication in its melody and harmonic progressions. Nonetheless, few seemed to appreciate his innovations, and the show produced no hit songs.

Another sticking point for the songwriters was the publishing arrangement for the songs. Working with their old publisher, Witmark, Eubie said they were lucky to get a $1500 advance per song; Whitney convinced T. B. Harms to pay an unheard of $5000 advance for the rights to The Chocolate Dandies’s numbers. However, the white producer pocketed all the money himself, claiming that it was part of the show’s proceeds. This was particularly galling to Blake. Harms quickly pulled the plug on the songs after the show failed, further limiting their success.

Perhaps disillusioned with commercial publishers, Sissle and Blake self-published a song in 1924 that was perhaps originally intended for for Chocolate Dandies:

the charming love ballad “You Ought to Know.” The publisher was listed as the “U.B. Noble Pub. Co.” on the U.S. edition of the sheet music—an unmistakable indication that they published it themselves. Eubie’s unusually sophisticated melody and harmonies forecast his later hit, “Memories of You,” and were far advanced for the period. When Sissle and Blake toured England a year later, they recorded the song for the UK market, but it was never issued on record at home. The sheet itself is fairly rare, indicating that it sold poorly on its initial publication.

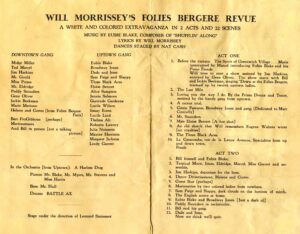

Will Morrissey’s Folies Bergere Revue

YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!

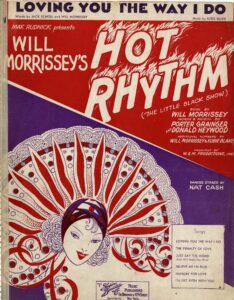

Blake was hired by producer Will Morrissey to provide music for his Folies Bergere Revue that premiered in Greenwich Village’s Gansevoort Theater in April 1930. Morrissey himself appeared in his revues, often in the audience, greeting the attendees while portraying an old-style Irish comedian. This mixed-race revue opened with a monocle-wearing announcer, sporting a faux-English accent, who introduced Eubie and his “Uptown Gang”: “whereupon Eubie treats the audience to a jazz soliloquy. A dozen or more mulattoes and octoroons, light of foot and gown flit in, do a congregational contortion, and flit out, to the delectation of the audience.” The New York Times critic was impressed with Eubie’s score, calling it “tuneful and catchy, and syncopated to a high degree.”

Eubie’s then-partner, singer/comedian Broadway Jones, was also featured in the show that—like many other theatrical revues of the day—was a hodgepodge of new and recycled material. Jones reprised his role in the satire of Green Pastures, a popular Broadway offering of the day, that had originally been part of Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1930. Blake and Jones also appeared towards the end of the second act to offer a sampling of their vaudeville act—just as Sissle and Blake did in Shuffle Along.

John Scholl—one of the original producers of Shuffle Along —was an investor in the revue, and may have suggested that Morrissey hire Blake to be part of it. He also encouraged Blake to compose some songs for the show, suggesting to Blake that he work with his young son, Jack, who had just graduated from college. Eubie recalled: “[Scholl] says to me one day… ‘I got a son, bores me to death, Eubie. He thinks he can write lyrics. Now get him off my shoulder. Go up and doodle something down.’ And he wrote the lyric and I set it. And the song hit. … Universal hit.”

The song they crafted was titled “Loving You the Way I Do,” and—of course—Morrissey added his name as lyricist along with Scholl’s son, Jack. The song was given a featured slot in the first act, appearing as #3 on the program. Although the show was a flop, the song was a hit, leading to Jack Scholl getting an offer to go to Hollywood, although he initially worked writing comedy plots, not song lyrics. Eubie ruefully noted, “Hollywood sent for him, [but] didn’t send for me, and he left me and he went out there.” Eubie’s anger that Scholl—a greenhorn—got a Hollywood job based on the song’s success while he lacked the same opportunity reflects the overall racism in the movie business. While a few black specialty pictures were being made, black composers had few—if any–opportunities to work for the major studios.